Michał Misiak — my activity in the studio gives me a great sense of fulfillment and happiness

You come from known artistic family. Did growing up surrounded by art, living in such an environment, influence your decision to choose this path? I know from personal experience how strongly this affects a person, because I considered it normal that in my home, art takes center stage. Did you have no choice because of your genes? Was it a dilemma for you? Was It a difficult decision, or simply a natural and obvious choice?

Indeed, a broad understanding of culture was always present in our home. It wasn’t just about visual arts, but also music, literature… Attending vernissages, visiting exhibitions, going to concerts was something natural. On the other hand, I grew up in a block in Nowa Huta, and my surroundings didn’t really concern themselves with such matters. However, my parents always supported my creativity, so I drew a lot and engaged in various creative activities. They never imposed anything on me, though. At some point in the second half of primary school, I took a break. It was probably some kind of rebellion, a period of greater identification with my schoolmates, who were completely detached from the world of culture. I was even at risk of staying in the same grade because I neglected assignments in art class... However, when it came time to choose a high school, I realized that drawing and painting were things that I was definitely best at. I got into the Krakow School of Fine Arts. I must admit, when I finished high school, I wasn’t yet aware that this was the path I would stay on. However, in my group of friends from school, we motivated each other quite strongly to engage in creative work. It seems to me that, for our age, we were quite involved in art, so it felt natural to aim for the Academy of Fine Arts. I wasn’t thinking about the future at that time. At that age, the peer environment often has a greater influence on a young person’s decisions than the example set by parents. So, to answer your question – yes, for many reasons, it was a natural choice.

How early did you start? Did they already put brushes in your cradle? :)

As I mentioned above, my parents always supported my creative activities. With their sensitivity and knowledge, they could see value even in the kinds of absurd actions that would not have been appreciated in the school environment. They always showed interest in my attempts to create strange, even pointless installations, and they could appreciate even seemingly clumsy drawings, seeing in them some kind of expression, a form of emotion… It was a great blessing because, despite the pressures from the school environment, this support allowed my awareness to develop relatively freely. Even during periods when the opinions of schoolmates and teachers had a greater influence on me, my parents' suggestions were always in the back of my mind. I can’t say exactly when I started. Some people are surprised, but the earliest image I remember in my life is simply the vastness of the blue sky, with tiny, barely visible specks floating. These are the tiny particles on the surface of the cornea of the eye that you can sometimes see when looking at a perfectly flat, non-contrast surface. I was lying in my grandmother’s garden, in a deep stroller. I think that’s when it all began…

Did your father’s presence, as both a well-known artist and a lecturer at your faculty, help or hinder your studies? Did it influence your studies in any way?

From today’s perspective, it’s hard to say why I decided to study at the Faculty of Painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow, where my father was a professor. Today, I would probably make a different choice. My father never took any actions to make things easier for me at university—that much I was sure of. Probably because I knew this, it was easier for me to decide to study in Krakow. However, such a situation is never neutral. The fact that I was a student of my parents' friends and colleagues wasn’t easy. On the one hand, I constantly worried that I was being treated with special conditions, and I didn’t want that. On the other hand, I put pressure on myself, thinking that my situation meant I had to achieve exceptional results. Thirdly, I imagine it was difficult for those evaluating me, making decisions about awards and distinctions, as well. Underestimating me could, in some people’s eyes, jeopardize their relationship with my father, while giving me too much recognition could lead to accusations of nepotism. Even today, in Krakow, where my father is a well-known and respected figure, I still encounter comparisons between mine and his artworks. It’s an uncomfortable situation. Maybe that’s why I’m more active outside of Krakow, even though I still live here.

At what point did you decide in which direction your artistic work would go? Was it during your studies, or did it come after a long search for your own path?

It’s hard to say exactly when I decided to pursue this particular creative path. There were many factors that influenced my decision, but there were a few key turning points. I'll return once again to my childhood and the benefits of having artist parents. Sometimes they would take me on trips or visits to exhibitions. When I was transitioning from primary to secondary school, my parents took me to Paris for about a month. The things I saw there permanently changed the way I looked at art. At that time, in high school, most of us were fascinated by Impressionist painting, and we mainly drew our inspiration from that period. I had high hopes of seeing the paintings at the Musée d'Orsay and other collections with works by the Impressionists. And I saw them, probably all of them. They were wonderful, but they only confirmed my feelings from earlier, when I’d seen reproductions of these works. The real discovery for me came with the works of Alexander Calder, Daniel Buren, some paintings by Mark Rothko, Ad Reinhardt, and Barnett Newman, which I saw at exhibitions and in public spaces. It was a whole new world for me, one that wasn’t really discussed in my environment at the time. From that moment on, nothing was quite the same for me. Of course, this didn’t mean that I immediately started creating works directly inspired by these artists. Many years had to pass, but from today’s perspective, I can see that this was one of those important turning points.

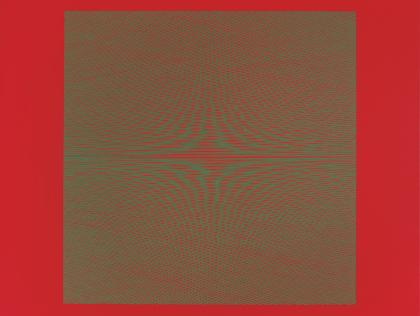

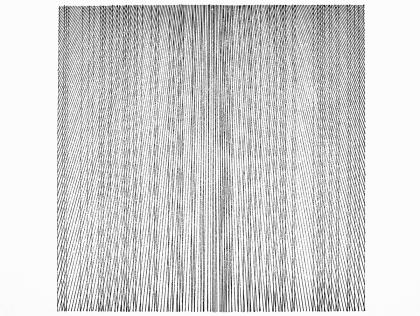

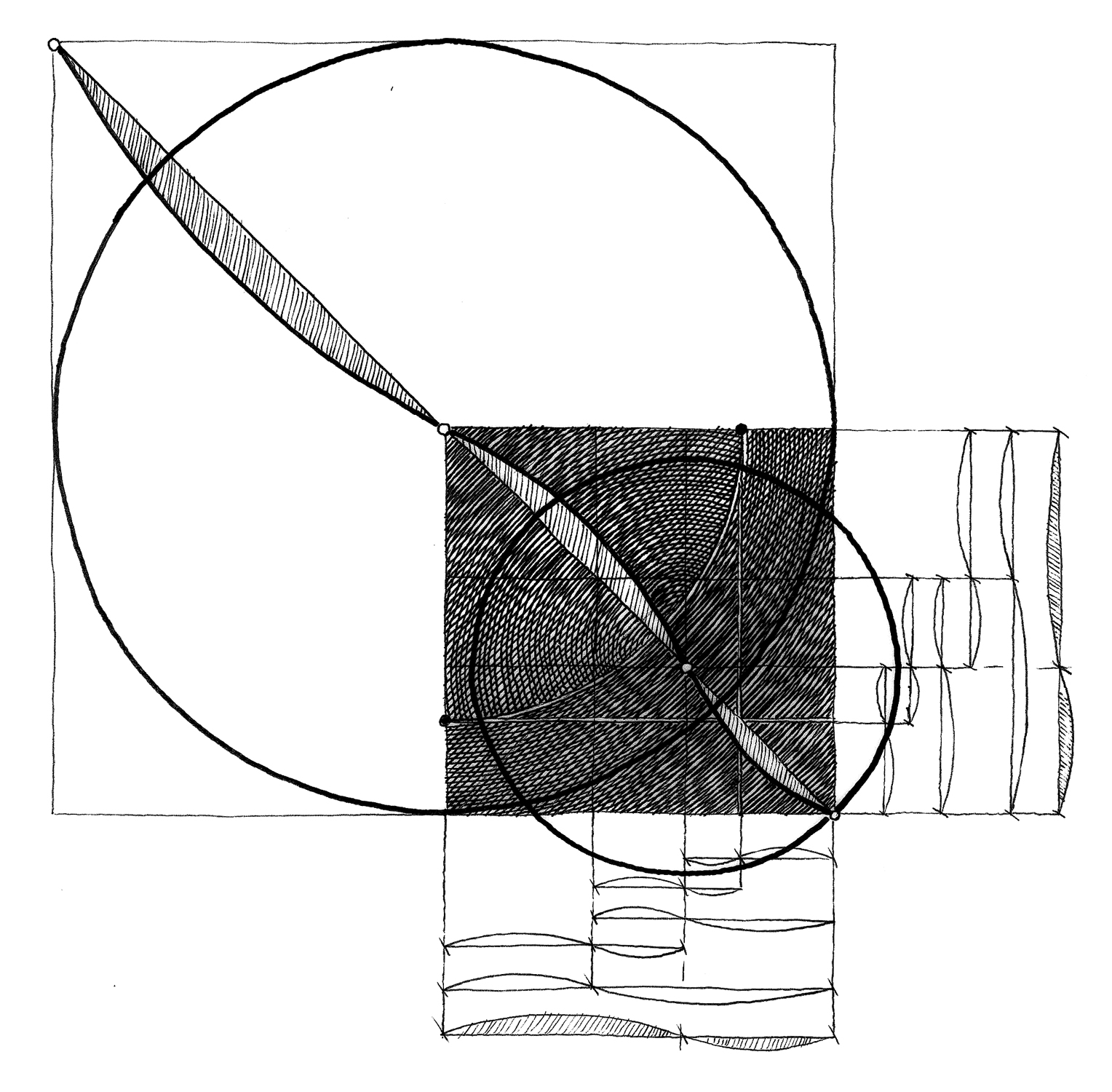

I studied in the painting studio of Professor Stanisław Rodziński, where the program was decidedly conservative. However, I was happy that the professor gave me a lot of freedom. At that time, my work was mainly focused on studying nature and gaining technical skills. But I was already showing a strong tendency towards form synthesis and reduction of expressive means. This was often met with criticism in the studio. At that time, just like today, art related to geometry was almost non-existent at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow. Outside my studio, which was focused on realistic art, there was a trend towards, broadly speaking, expressionist work. My classmates exchanged albums of works by Markus Lüpertz or Georg Baselitz. I also somewhat fell under these tendencies, though expressive painting never really came naturally to me. In my third year, I joined the woodcut studio led by Professor Zbigniew Lutomski as part of the elective studio. I now think that this was another pivotal moment. I would bring my sketches of nudes or landscapes, drawn in heavy pencil or color, and he would give me the challenging task of translating them into radical black-and-white linocuts. I remember reading an interview with Jerzy Pankiewicz, who was asked why he often made colored sketches with crayons or markers for his black-and-white prints. He replied that he transferred the color into black and white because the color would still be there, even though the final print was monochrome. That left a lasting impression on me. These memories may seem like insignificant details, but from today’s perspective, I see how important they were. So, in order to transfer this color into the black-and-white language of linocut, I began creating matrices made of dense, parallel lines. As I developed this method, more complex and larger compositions began to emerge. Along the way, I found that the process of creating these prints—long and laborious, made up of repetitive movements—became deeply engrossing. It was like a kind of meditation—I lost touch with reality and felt as though I had moved somewhere else. It gave me a sense of peace and fulfillment.

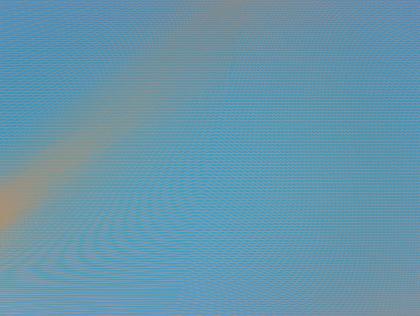

My master’s diploma in painting was accompanied by a supplement in the form of large-format linocuts. For another two years after graduation, I painted landscapes or figurative compositions, somewhat lost and unsure of where to go next. At the same time, I was creating prints that gave me more satisfaction and a sense of certainty that this type of work was more suited to me. However, I loved painting, so I couldn’t simply abandon painting for printmaking. Eventually, I began looking for ways to transfer the language I had developed in printmaking into painting. It was also about this, let’s call it, ‘conceptual’ aspect. I began to see and believe that through this meditative process of creating my works, I had a chance to convey to the viewer a hint of a special state of mind that made me happy. In 2001, the first painting from the "Horizon" series was created, built from structures of dense lines. This painting now hangs in the office of the Department of Fine Arts at the Faculty of Interior Architecture, where I work.

Surely, pursuing art, especially deeply personal and independent work, and following your own artistic path, hasn't been and still isn’t easy. Does it bring you happiness? Could you live without creating?

I feel that my creative practice is the most important thing for me. Of course, family is important too. Balancing these two areas is a difficult task, especially when the chosen creative method is so time-consuming. That’s why I give up many activities in my life. Frequent social meetings, participation in the so-called ‘artistic life’ of the city, and travels unrelated to creative work—these are things I have to set aside. However, I don’t feel like I’m losing anything. My activity in the studio gives me a tremendous sense of fulfillment and happiness. I try to be in the studio every day. I treat my work as a daily practice, rather than a series of individual projects.

Have you ever considered what you might do if it were something other than what you are currently doing?

Music, or the world of sound in general, plays a very important role in my life. It is a source of endless inspiration for me, which I transpose and realize in the realm of visual art. I have never studied it, but I believe I have a good sense of hearing and a sensitivity to sounds. This has both positive and negative effects. Sounds bring me great pleasure, but at the same time, I am quite demanding in this area. I suffer from the acoustic pollution of the world. If I were to do something else, it would certainly be something related to sound, music.

What determines that you work on a particular series (for example, in a chosen color palette)? Is it an impulse or a carefully thought-out concept?

New composition ideas often take a long time to mature—sometimes several years. Very often, the painting process is preceded by ink drawings, followed by small painting trials. Once these are created, I often put them aside for a longer period to check if they become outdated. After some time, I return to them. This relates to the fact that creating paintings takes a long time. During the painting process of current works, ideas for future ones arise, and I need to note them down. I don’t usually plan out entire new series of works in advance. The naming of a series and its identification as a cycle often happens only when a group of works is already finished. At that point, I notice that, for example, they share something special that allows me to group them together under a specific title and to continue working on them more consciously. Yes, in some series, there are certain pre-established assumptions. This was the case, for example, in the series based on the idea of the golden ratio, or others created using a random number generator. Generally speaking, I think of my works as layered structures. One of those layers is the geometric structure, often based on simple mathematical principles or some other strict assumption. The second layer is color, which belongs to the world of intuition and difficult-to-explain choices. Overall, my work is never impulsive or revolutionary. It is rather a slow evolution, with stages unfolding over time. Each subsequent stage is like another line in a particular painting. In this way, the entire process has a wave-like, rhythmic quality and is, in some way, repetitive.

You are one of the most highly regarded and well-known contemporary Polish creators of geometric art. Your paintings and spatial structures are, in themselves, an unmistakable signature—strongly recognizable. At the same time, you run the Struktury Działań Przestrzennych i Barwy(Structures of Spatial Actions and Color) studio at the Cracow Academy of Fine Arts, where you implement your own educational program, which for me is very much aligned with your artistic journey. What significance does this have for you, and does this activity also influence your broader personal development?

I am very pleased that you perceive the activities within the Struktury Działań Przestrzennych i Barwy studio as aligned with my creative work. In my view, teaching at the Academy of Fine Arts should be closely tied to the creative activity of the artists working there. I cannot imagine it being otherwise. Above all, my own artistic practice legitimizes me to work with students. The most important thing is being open to the students' sensitivity while also sharing my own experiences with them. These personal experiences are the most valuable thing we can offer them. For me, working in the Struktury studio is also a bit like an experimental laboratory. By giving students various tasks to solve, I carefully observe them. I am fascinated by how they sometimes come up with solutions in surprising ways. There are times when a particular problem has been bothering me, and I am looking for solutions. It happens that the students tackle this very same issue, and I find great joy in that—it’s something I draw from. I learn from them a sense of freshness and freedom. I think this works both ways. I must admit that the experience of leading this studio has in some way influenced the path of my own creative explorations, and vice versa. In the implementation of the studio program, I primarily focus on the students' artistic creation, regardless of the fact that the tasks I set for them are dedicated to very specific phenomena. This is also something that fascinates me and that I engage with—operating at the intersection of strict laws and unrestrained freedom. The laws of color perception or the relationships of forms in space are often subject to revision. The students become familiar with them and have the right to respond to them through their own creativity. Sometimes they contradict them, and that is very valuable as well. I believe this is particularly important for future designers.

...I began to see and believe that through this meditative process of creating my works, I had a chance to convey to the viewer a hint of a special state of mind that made me happy.

Your works require focus and precision. How much time does it take you to complete a painting? Do you work on several paintings at the same time, or just one at a time?

My way of working requires me to work simultaneously on several projects. Some are still in the early conceptual phase, while others are at various stages of completion. This partly also relates to technical reasons. I love working in oil paint. The successive layers and stages take a long time to dry. During that time, other works are developed. It’s rare for a piece to be completed in less than two months.

You are constantly searching—experimenting with very unconventional image formats with highly contrasting side lengths, and now also spatial works. What drives your constant quest for something new?

The search for something new, in a sense, is part of every creative activity. I don’t feel that I stand out particularly in this regard. There are those who make the search for novelty the main purpose of their artistic endeavors. I’ve never placed that as my primary goal. My experiments are innovative more in the context of my previous work, rather than in the broader scope. They arise from pure curiosity and playfulness. The unconventional formats you mention were created mainly for the exhibition Frequencies at the Dystans Gallery in Kraków. When preparing an exhibition, I always think about the arrangement of the space—it’s important to me. I feel that my paintings should engage with that space in some way. So, I thought the space would need elements that would introduce some kind of contrast, while still fitting within the current series. I think I managed to create proposals that meet these criteria, though today it seems to me that the idea of these long paintings is mostly closed. Very elongated, narrow formats no longer work as a flat image. They act more as a space around the work. They appropriate and organize that space, somewhat like architectural elements—columns, pilasters. Such formats also appeared, for example, in Barnett Newman’s work in the 1950s. For him, they took the form of a vertical line extracted from his earlier works. The role of large color fields was taken over by the surrounding space, which became involved in the composition. However, I never have certainty whether I might return to certain kinds of work. I consider all the cycles of my paintings to be open, and I allow the possibility of revisiting them, continuing them.

Could you reveal what’s new on your mind? Can we expect more surprising experiments?

I wouldn’t want to talk about things I still don’t know much about. New works are being created, probably in some ways a bit different from the previous ones. The exact nature of that difference will become clear later. Right now, I’m thinking about an exhibition I’ve scheduled for a year and a half from now. That’s how long my preparation process takes. Everything is still in progress, and I’m not sure yet what will come of it.

Which exhibitions or collections, in which your works have appeared, are the source of the greatest satisfaction for you?

There are several places where my works are present, and they bring me a sense of joy and fulfillment. Certainly, these include the collections that were created in connection with the Plein Airs for Artists Using the Language of Geometry, organized by Dr. Bożena Kowalska. These collections were established in three locations – at the Museum in Chełm, the Center for Polish Sculpture in Orońsko, and the MCSW Elektrownia in Radom. My works are present in the last two of these collections. These collections reflect Dr. Kowalska's curatorial vision and are meticulously conceived, featuring works by outstanding artists. They hold great artistic and historical value. My works can also be found in several significant private collections. One such place is the Museum Jerke in Recklinghausen, Germany. The owner, Werner Jerke, has been collecting Polish art for many years. He built a museum in the center of Recklinghausen, which is the first museum presenting Polish art outside of the country. It is an excellent collection, including many works by outstanding Polish artists from the 20th and 21st centuries. The owners of some private collections periodically organize exhibitions, thus making their contents available to the public. A prominent example is the collection of Grażyna and Jacek Łozowski, which has been shown in recent years at the City Museum in Wrocław, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Olomouc, Czech Republic, and the State Gallery of Art in Sopot. Recently, my works have been added to the beautiful collection of Mr. Michał Molski in Poznań. This collection also has its own gallery building, which was recently opened. I am pleased that my works are present in these mentioned places because their owners base their choices on knowledge, a coherent concept for creating a collection, and great intuition. As a result, these collections contain many outstanding works

Has it ever happened that something in the reception of your works, or in the reactions of the audience to them, surprised you? Perhaps some interpretations that you didn’t expect?

In my works, I try to ensure that, despite their physical nature, it is possible to transcend the barrier of physicality during the process of reception. Once, a friend of mine, also an artist but working in completely different areas of art, saw the structure of denim fabric in my paintings. At first, I was worried — I thought it wasn’t working the way I intended. Today, I want to be open to such unexpected interpretations. I would like my works to operate on various levels, although, of course, there are those that are the most important to me.

You're currently participating in the international exhibition 'Connection Bożena.' Could you tell us more about the theme?

The exhibition “Connection Bożena” is closely related to the International Workshops for Artists Using the Language of Geometry, created and curated by Dr. Bożena Kowalska. She is an incredibly significant figure in Polish culture, the author of numerous books, articles, and publications on Polish 20th-century avant-garde art, as well as on the biographies of artists connected to the geometric art movement. The workshops she founded have been taking place since the 1980s, with the most recent, the 36th, held in 2018. I had the great honor of participating in these annual gatherings since 2004. The exceptional charisma and uncompromising nature of the curator meant that leading artists from many countries involved in this movement attended the workshops. For many of them, Bożena Kowalska’s presence and the annual meetings with an international group of artists became incredibly important. Bożena herself refers to this group of artists as “her geometric family.” During the years I had the pleasure of attending, these workshops were more in the nature of symposia. They weren’t so much about creating works of art, but rather about intense discussions on art, participant presentations, and lectures. It was during these workshops that many connections and friendships were formed, laying the foundation for future projects and exhibitions. Events stemming from these meetings and the relationships formed there occasionally take place in Poland and across various parts of Europe. The “Connection Bożena” exhibition is one such event, inspired by the unique phenomenon and atmosphere created by Bożena Kowalska. The curator of the “Connection Bożena” exhibition, German artist Martin Vosswinkel, was also a participant in the workshops. This exhibition is his tribute to the remarkable curator and yet another opportunity for the artist friends to gather and meet in the realm of art.

What are your upcoming plans? Where will we be able to see your work?

I wouldn't want to reveal too much about my plans. Recent times have shown that they can undergo unforeseen changes. I prepare exhibitions over a long period of time. Currently, I am starting work on a show that will take place in the fall of 2024. I hope we will meet then, among my works, in Łódź.

Thank you very much for the conversation.